Part I: The Untold Stories of TOTVS, the Largest Software Company in LatAm

Back in the 80s, Bill Gates predicted that every home would eventually have a computer. Prompted by this, Laercio then wondered: how many computers would a company own?

Laercio, alongside Ernesto are some of the most successful Software entrepreneurs of our time, having built TOTVS (BVMF: TOTS3), the leading ERP vendor in Latin America. It may be flying under the radar outside of Brazil, but TOTVS is the indisputable unsung giant in the region. Their story and their journey are among the titans of the tech industry.

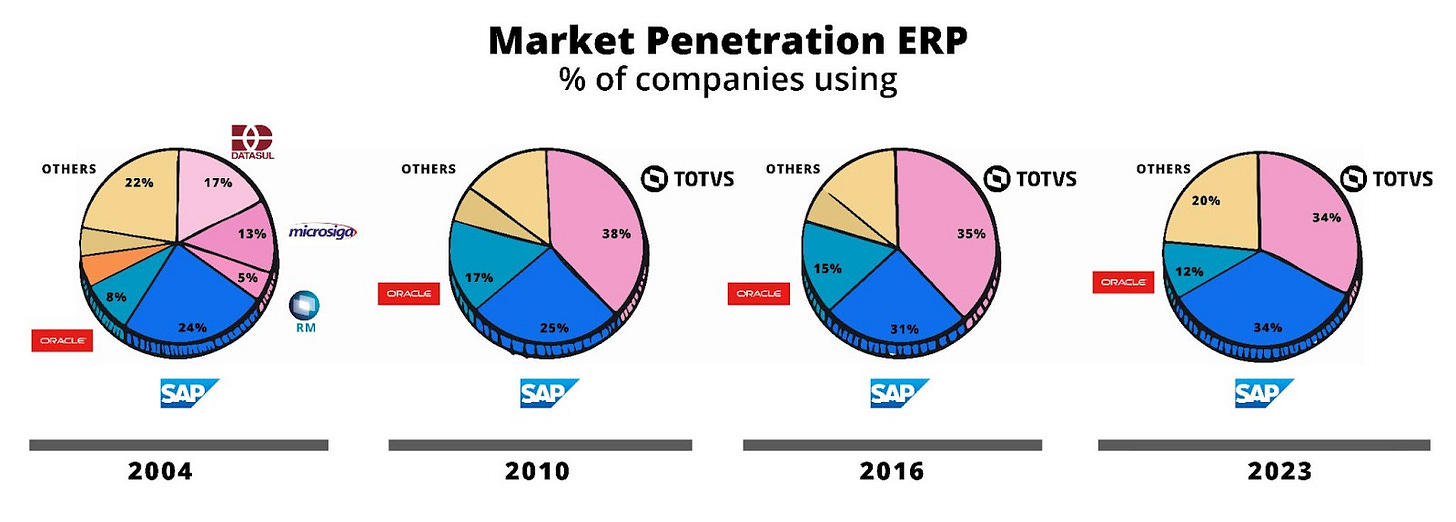

It is impossible not to put TOTVS in the race to compete with its ERP counterparts. With 34% of the market share in 2023, the company is a notable local challenger to giant global competitors SAP and Oracle. In Q3 2023 alone, TOTVS reached R$ 1.2 billion (~ US$250M) in Net Revenue, with 19% growth YoY.

Having three main clusters of revenue streams, the “Management SaaS” alone - which comprises their core SaaS and Cloud services - generated R$ 1,038 billion in revenue (~ US$216M). Meanwhile, their “Biz Performance” unit generated R$ 115,4 million (~ US$24M), and their newly inaugurated joint venture with Itaú (the biggest bank in Latam) called “Techfin” generated R$ 97,8 million (~ US$20M).

TOTVS is also a top-performing company when it comes to generating profits. In Q3 2023 they were able to increase their Cash Earnings margins by 28,9% YoY and reached an impressive amount of R$ 214,8 million, representing a net margin of 17,9%.

It's not by chance that the world is looking at TOTVS. In March 2023, Fitch affirmed 'AA+(bra)' rating towards the company, praising its capacity for generating new businesses while diversifying its solutions portfolio and generating positive cash flow in uncertain macro scenarios.

TOTVS started as a small software house in São Paulo, Brazil, to become one of the most relevant software companies in Latam and the world. And they did it on the hard mode even before VC was a reality in Brazil.

The company is the ultimate example of an untold story of how a handful of Brazilian entrepreneurs, in the first days of hardware and software, were able to build a world-class tech behemoth.

Not only were they pioneers in developing new technologies for businesses, but they also created investment attention that would be important for entrepreneurs in the tech industry for decades to come.

It all started with naive and ambitious desires, and it became the dream of many entrepreneurs nowadays. Here's their story from their perspective:

The software market in the 1980s

Back in the 1980s, there were zero Venture Capital firms actively deploying capital in Brazil. It means that while Larry Elisson was pitching Oracle to Don Valentine at Sequoia, Laercio Cosentino, and Ernesto Harberkorn, the founders of TOTVS, were fighting for every customer dollar. It was especially difficult with the macro climate in Brazil at the time. The currency in Brazil was the Cruzado and its accumulated inflation reached 364% in 1987.

Nowadays, if compared to the 1980s and 1990s it's easy to get stats to plan for an audacious goal. Access to information is abundant and only a couple of keystrokes away. However, it was an immense challenge to launch a company with limited information and no external capital. The barriers to entry were much higher than they are today and internet access was almost nonexistent.

The internet had not yet reached significant penetration - having arrived only a few years before in 1981 - and it was difficult to sell investors a vision of the future we are today. In the year 2000, while internet penetration in the U.S. was at 43%, in Brazil it was reaching only 3%.

Even with the challenges back then, Ernesto and Laércio didn't back down. Instead, they saw the challenges as an opportunity to march ahead and build what would become one of the most impressive tech companies in the world.

Ernesto's Odyssey: Pioneering Software in Brazil

When reading and watching everything about Ernesto Haberkorn, you'll notice how inebriating it is to be around him and his positive attitude. From the best of his 80 years, he seems unstoppable, running multiple projects at the same time while making sure he's being of value at every waking moment.

Ernesto started his career at Deca, a plumbing parts manufacturer company. The opportunity to work there turned up as he got his business administration degree in 1964 at Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV-EAESP), one of the top business schools in Latam.

Business schools were so incipient that he felt he was being conned by the school. It was a waste of time to spend so much time studying something that appeared to be, as he describes, ridiculously common sense.

As a business bachelor, he left business school hungry to apply his knowledge. His first job was to calculate the costs of every single part that goes into plumbing mechanisms. His boss, seeing how much time that took, presented him with a solution that would open his eyes to a whole new world. He took young Ernesto to IBM, where all of the taxes from the plumbing company were done.

When seeing an IBM 1401 and the punched cards for the first time, processing hundreds - maybe thousands - of documents in a few minutes, Ernesto felt the joy of discovering something so impressive that would change his life.

The next day Ernesto signed up for his first coding course. The programming language was Assembly, "a way better language than the terrible Javascript I'm learning now", as he later describes.

After leaving Deca, Ernesto started developing financial planning systems in every place he worked. One day, while working at Siemens, he found out that the company was going to shut down operations in Brazil. He then asked his boss if he could implement the software he invented in a friend's company, to which his boss skeptically replied: "Well if the system works one day… you can, sure".

There's nothing like scratching your own itch to start something of lasting value. This was only the beginning of a love story between Ernesto and software development that led him to build his own company: SIGA.

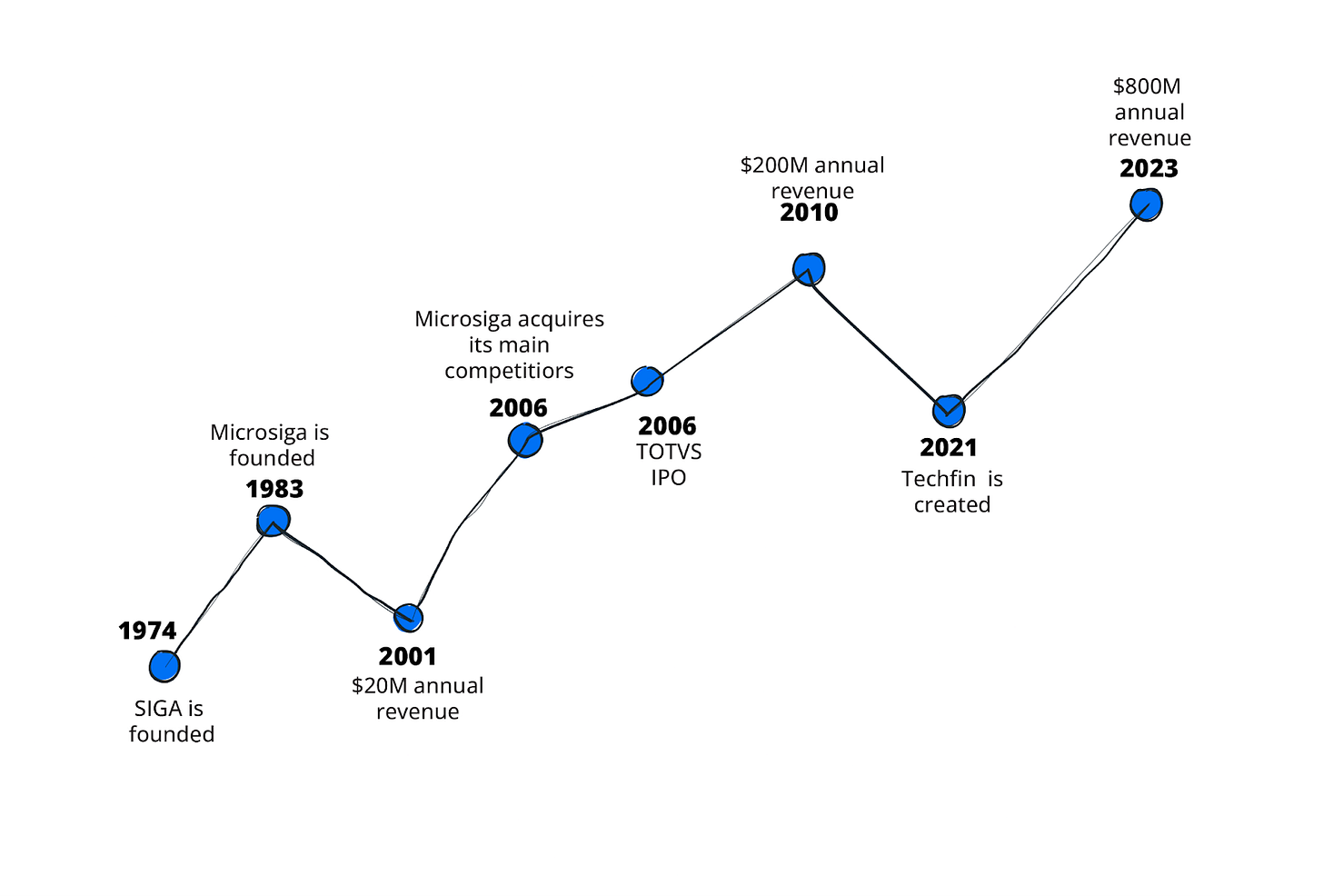

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) was already a reality outside of Brazil. But until then, in 1974, Ernesto's ambition was to build his own company and become a successful entrepreneur to live off of his work comfortably.

And that's exactly what he did by growing a one-man business to a 50-employee software house that had a shy but increasing presence among small businesses in Brazil.

Ernesto's Apprentice: Laércio Cosentino's Climb from Intern to Industry Titan

Somewhere else in São Paulo, a few years before the birth of SIGA, Laércio Cosentino was a young man who was getting interested in business early in life. But he had no idea it was called business at the time. It was almost impossible for him to have such a grasp as a 9-year-old. However, doing debt collections for his family's tiny grocery shop taught him a few lessons.

That aspect of him flourished early and lasted for all his youth. One of the first deals he made as a young man was with his own father. He asked his father to pay him half of his tuition as a salary if he could get admitted to a university where tuition wasn't necessary. Needless to say, that's exactly what happened. Laércio got into Universidade de São Paulo (USP), one of the most competitive universities for engineering in Latam.

Laércio was still in college when he joined SIGA, the 50-employee software house in São Paulo founded by Ernesto, as a software development intern. He didn't get a salary when he joined SIGA, but that didn't make him less motivated.

When Laércio joined, his fast-learning abilities quickly caught up to realize the management system of the company was inefficiently vertical. All employees reported directly to Ernesto Haberkorn, his (and everyone else's) boss. Little by little, Laércio became essential to the business, slowly accumulating responsibilities (and power) and convincing Ernesto to let him take care of core business areas.

In a 2 year stint, he went from an unpaid intern to running a meaningful part of the company’s operations, including sales, which he considered to be the heart of the business.

Ernesto, his boss at the time, was an entrepreneur managing his business long before the ambitious young intern came into the picture. Even though Ernesto knew his company was inefficient, he didn't think there was an urgent need to change anything. After all, if it wasn't broken, why fix it?

His boss's fixed mindset didn't stop Laércio from going from an intern at 18 to director at 23. After winning many battles to restructure the organizational management of SIGA, Laércio knew there was still a long way to go.

Laercio had figured out a clear opportunity. It all started with a simple, but ambitious perception: "When Bill Gates said that every home would have a computer at home, imagine how many computers would a company have?"

Laércio had the ambition to drive that venture's future growth. The company’s entire business was shifting from mainframe computers to microcomputers, and unless they became an entirely new organization, they would go out of business.

He had a bold vision. He wanted to be part of something he could have real ownership of. To make the vision a reality, he invited his boss to an apparently casual lunch.

The meeting started with Laercio selling the vision he had for a transition plan. He wanted to agree with Ernesto on a new programming language and business plan. Laércio even went ahead and made a new logo, under a new name, Microsiga.

With a lot of push and pull, Laércio started the conversation by proposing to own a fraction of the company but amidst the conversation, he insisted that it would only work if he and Ernesto became equal partners in the new venture.

Laércio knew where he wanted this conversation to end up. So much so that he already had a typed contract in his folder for him to sign at that very dinner table, written: 50% ownership for each of the partners.

The plan proposed by Laércio was to take over Latin America with their new software: Protheus. They defined the new programming language (what it would do, how it would do it, and why they should use it) and how it would go to market. But despite the bold vision, little did they know that the partnership Laércio was proposing was going to change both of their lives forever.

To make the plan work, back in 1989 Laércio and Ernesto realized that they needed to expand their geographic presence. If it hadn't happened at the time, one of their competitors would've done it in their place. So, in that year, they started something completely daring for the time -- a novel plan for expansion through franchising.

Despite being told by seasoned professionals in the tech industry that the franchise model would not work, they committed to expanding software sales through franchising throughout Brazil. That plan multiplied revenues by 10x, conquered the country, and proved that the franchise model was beyond ambitious at that moment.

However, Laércio describes this time as one of the most challenging parts of his career. Working without much help, spending 50% of his time programming and the other 50% doing everything else, he had to prioritize.

"In the beginning, I had to do everything. I was a hands-on guy, doing a little bit of everything — programming, traveling, doing customer service […] So in 1994 I stopped programming software. I needed to focus on making the company expand."

The franchise model was the foundational stone of the business. But something was missing. To grow faster and challenge competitors, Laércio realized he needed to increase Microsiga's awareness internationally. Only one thing would do it: partnering with a well-known global Private Equity firm to take the company to another level.

"I wanted the company to grow faster and gain even more confidence in the market. The negotiation was difficult and there was even a moment when I thought about giving up [...] I talked to 12 funds until I reached Advent International, an alternatives powerhouse that up to these days holds over 90 billion in assets under management. It certainly would add important credibility and help Microsiga grow”.

Having Advent onboard in 1999 meant they were ready to fight global giants of the software industry. It was a stepping stone to go even further. By that time, they had already conquered a lot of territory in Brazil, fighting with international behemoths such as SAP and Oracle.

Fast forward to today, this is TOTVS' market share in Brazil, against its counterparts in the ERP vertical:

Partnering with Advent International paved the way for a master plan that included Microsiga’s preparation for a public offering in the former BMF&Bovespa, São Paulo’s stock exchange now called B3.

Laércio and the team did everything to make sure governance was on point to take the company public. They spent 2 years preparing for this move until 2001 when a plane hit the World Trade Center and turned Microsiga's IPO roadshow in the U.S. into a plan B.

It was time to regroup.

The Road to the IPO

Zé Rogerio, the rally navigator

When José Rogério Luiz, or Zé Rogerio, joined the company, Microsiga was beyond walking with its own two legs. It was running fast, selling close to R$100M (~US$34.4M adjusted for inflation from 2001 to 2023) yearly. However, it was difficult to improve margins at the same pace as the company grew.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Microsiga had a 10% EBITDA margin and was plateauing on a 5-10% yearly revenue growth. Domestic competitors such as Logocenter and RM Sistemas were challenging Microsiga's deals and growth was getting more and more challenging. Laércio was a man at a crossroads. It was time for a strategic change.

Already this far in the game, Laercio was proud of having built his business from nothing into a company with a respected name. The ERP market seemed to have achieved meaningful maturity and he was struggling to return to accelerated growth. He knew that he couldn't do it alone. He needed someone to help him lead it into the future—and luckily for him, he found Zé Rogério.

When Zé Rogério met Laércio for the first time, he could sense how much passion Laércio had for his business and how much potential it held. Although he had never worked with anyone like him before, he knew that together they could take Microsiga to new heights.

At the same time, Laércio knew that Zé Rogério wasn't just some lofty executive with a head full of big ideas — he seemed like someone Laércio could work with, grow alongside, and learn from.

Before joining Microsiga, Zé spent a decade working as a banker at Citi and later made his name as the CFO of Grupo Antarctica during its merger with Brahma, two behemoths in the brewery industry. This transaction led to the creation of Ambev, which was the largest brewery in the world at the time and later morphed into AB InBev.

When Zé Rogério entered the company, he identified two core issues holding Microsiga back: the company's franchise system wasn't working as well as it could have been, and Laércio himself was too focused on the operation, with little time to take a step back and think of new growth levers for the company.

It was difficult for Laércio to take that step back and see the bigger picture. He was already running the company for 15+ years. He had to let a new driver take the wheel, while he was still stepping on the throttle.

Laércio was proving some of his own medicine. It was the same medicine he had given Ernesto in the past, and it was an arduous task for him to take on. But it was time to step aside from strategy and open space to the rally navigator.

Zé Rogério presented a transition plan to Laércio that would take Microsiga from R$100M in revenue (~$34.4M adjusted for inflation) and a 12% EBITDA margin to R$250M (~$86M adjusted for inflation) in revenue in 4 years, a 2.5x revenue growth and 2x margin increase to 24%. When compared to its domestic counterparts, RM and Logocenter, Microsiga was already one of the main players in the ERP market in the region.

It was just the beginning of the master plan to put Microsiga on the R$ 1 Billion (~$344M adjusted for inflation) revenue path. Their competitors could not fathom how strong the power of Microsiga's momentum was.

Besides the competitors mentioned before, there was one that Microsiga was particularly interested in overcoming, Datasul. Its principal was Paulo Caputo, a self-made developer who learned to code when he was only 15. Paulo graduated as a lawyer at the Faculdade de Direito de São Paulo, then built a career as a Corporate lawyer at Machado Meyer.

When Paulo joined Datasul as the CFO in 1999, his mission was to prepare for receiving funding. He never knew Microsiga would become the competitor it did a few years later. In one of his first meetings at Datasul, he asked a team member what "Microsiga" was, to which he got: "Don't worry, they're not a competitor."

Datasul was one of Laércio's rivals. He saw in this competitor not only his way to winning the Brazilian ERP market but a clear opportunity to go toe-to-toe with international software vendors such as the giants of the industry, SAP and Oracle. To one day achieve enough relevance to be compared with them, there was only one milestone that would do: reaching R$ 1 Billion (~$344M adjusted for inflation) in revenue.

Getting The Ducks in a Row

Zé Rogério and Laércio understood they had to consolidate the local ERP market. There were too many players competing for customers and this was terrible for everyone. The first idea from Zé Rogério was to make sure that these players were talking among themselves. To do so, they created the "Software Alliance". An association formed by the biggest four ERP players in Brazil – Microsiga, Datasul, Logocenter, and RM.

The group's ritual was simple: the heads of the 4 Alliance members were going to meet regularly at a hotel, coming one at a time, at different times not to raise any eyebrows, to talk about the development of the sector in Brazil. The last one to leave the meeting would pay the bill. That was always Laércio.

This was an incredible exercise for all involved. It was great to finally put everyone in a room to make sure they were all rowing to the same side and develop a fruitful ecosystem to offer technology for small and medium businesses. These regular meetings started creating a closer relationship between these brands and they were on a path to consolidate a fragmented market.

Laércio kept thinking after those meetings that he had to make things whole. The status quo wasn’t working anymore. He finally understood, together with Zé Rogério, that to reach their audacious revenue goal, they had to reorganize the whole industry.

The rally navigator and the ambitious founder then had an Eureka moment. They had to start lining up the ducks. They concluded that there could only be one winner in the ERP market at that time. The Highlander's mission was to acquire the main competitors, but first, they needed to do some cap table cleaning.

In February of 2005, TOTVS had its D-Day. What they did was a master play only fit for a select few. The kind of deal-making done is worthy of an award, if they gave one.

In 24 hours the company bought back the shares of Advent Internacional, acquired one of its main competitors, Logocenter, and welcomed a new investor.

The first transaction that made Microsiga's revenue grow by 25%, was the purchase of Logocenter.

This set the ground for a new transaction that very day, which was getting funding from the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). They received R$ 40 million for 17,6% that day, making BNDES a shareholder of the company.

To buy back Advent International, Laércio had wisely set terms for future buyback since the day Advent joined their cap table. And so he did, buying their shares back, growing the company by 25% with a financial play only fit for a selected few while neutralizing an important competitor.

Microsiga and Datasul would then fight for the 1st place in software sales in Brazil. To be there alone, one of these companies would have to acquire their competitor, RM. It was a similar challenge for both Datasul and Microsiga. Both of them had to raise capital through an IPO to finally acquire RM, but Microsiga had the jumpstart and started negotiating the acquisition pre-IPO.

Laércio and Rodrigo Mascarenhas, founder of RM had many back and forths about the acquisition price but finally agreed on the number: R$ 164,8 million with another R$ 41,2 million depending on the accomplishment of some goals. It seemed a bit bitter to swallow for Rodrigo, but he was willing to do so.

Microsiga had it in the bag. They could IPO and go after Datasul later with much more resources. They had the plan and the deal ready.

On March 9, 2006, by the BM&F BOVESPA opening bell, Microsiga became TOTVS, which translates as "totality" in Latin, went public, and announced RM's acquisition, consolidating itself as the main software developer in Brazil.

Amazed by the master play, 2 years later Datasul decided to sell to TOTVS, the company that in just 3 years went from R$173M in annual revenue to an astonishing R$734M in 2004, growing 4x in this period and showing to everyone that TOTVS was the meaning of "everything".

PART II coming soon...

This is the second edition of a series called Giants of SaaS Latam, a series portraying the untold stories behind the most valuable SaaS companies in the region. When it comes to solving complex problems with astonishing elegance, Latam founders are able to build long-lasting, solid businesses.

TOTVS' story was made by Latam founders and executives who challenged an incipient market and helped inaugurate the internet in Brazil. Its story is now told by William Cordeiro and Leo Torres, authors of this essay.

William is the Managing Partner of SaaSholic, a venture capital firm that specializes in investing in early-stage Latin American SaaS companies, having raised $10M+ to invest in ambitious founders building category-defining businesses from idea to IPO and beyond. To date, SaaSholic is at their second fund, with a portfolio of 30 startups such as Conta Simples, Clicksign, Yooga, and Acquire.com

Leo is the author of I’m No Economist, a newsletter covering global investment trends. Despite not being financial advice (Take no advice from me. I’m No Economist) the newsletter is read by investment professionals across VC, PE, M&A, family offices, and tech entrepreneurs.

A special thanks to those who participated in telling untold stories for this essay – including investment analysts from renowned firms that preferred not to be mentioned.